Missing You Convince Myself Get Over You Baby Crying Mom Singing Ellen

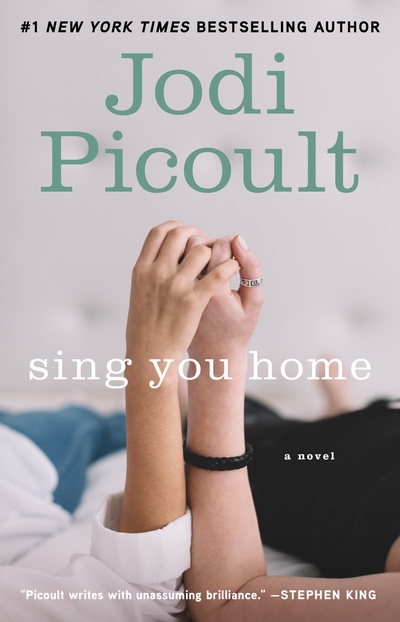

Sing You Home

Sing You Home explores what it means to be gay in today's world, and how reproductive science has outstripped the legal system. Are embryos people or property? What challenges do same-sex couples face when it comes to marriage and adoption? What happens when religion and sexual orientation – two issues that are supposed to be justice-blind – enter the courtroom? And most importantly, what constitutes a "traditional family" in today's day and age? …more

Sing You Home is a compelling story by a writer capable of influencing peoples' opinions on this important subject.

Listen to the Sing You Home soundtrack!

Listen to the Sing You Home soundtrack (10 songs). If you are a Kindle, Nook or eBook user who can't access the music on your e-reader, you can still enjoy the songs! Simply click the red arrow to play.

Ellen Degeneres chats with Jodi Picoult about Sing You Home

The Story Behind Sing You Home

Sing You Home extras: research, music therapy, CD lyrics, gay rights information and resources

ABOUT

About Sing You Home

Zoe Baxter has spent ten years trying to get pregnant, and after multiple miscarriages and infertility issues, it looks like her dream is about to come true – she is seven months pregnant. But a terrible turn of events leads to a nightmare – one that takes away the baby she has already fallen for; and breaks apart her marriage to Max.

In the aftermath, she throws herself into her career as a music therapist – using music clinically to soothe burn victims in a hospital; to help Alzheimer's patients connect with the present; to provide solace for hospice patients. When Vanessa – a guidance counselor -- asks her to work with a suicidal teen, their relationship moves from business to friendship and then, to Zoe's surprise, blossoms into love. When Zoe allows herself to start thinking of having a family, again, she remembers that there are still frozen embryos that were never used by herself and Max.

Meanwhile, Max has found peace at the bottom of a bottle – until he is redeemed by an evangelical church, whose charismatic pastor – Clive Lincoln – has vowed to fight the "homosexual agenda" that has threatened traditional family values in America. But this mission becomes personal for Max, when Zoe and her same-sex partner say they want permission to raise his unborn child.

Also – in a very unique move – readers literally get to hear Zoe Baxter's voice. I've collaborated with Ellen Wilber, a dear friend who is also a very talented musician, to create a CD of original songs, which correspond to each of the chapters.

The publisher: Atria Books, 20xx (Book )

THE STORY

A conversation with Jodi about Sing You Home

The story behind Sing You Home

My first crush was on a boy named Kal Raustiala when I was in second grade. He had shaggy, leonine hair and a pet iguana and a jungle gym in his basement. Although I didn't really know why at the time, my heart beat faster near him. When he wasn't around, I wanted to be with him. And when I was with him, I never wanted to leave.

At no point prior to falling hard for Kal did I choose to be attracted to a boy. It just sort of happened, in the way that love often does: naturally, instinctually, and whole-heartedly.

After college, I had a friend who, like me, was naturally, instinctually, and whole-heartedly attracted to boys. His name was Jeff. My roommate and I spent many Friday nights with Jeff and his partner Darryl, catching the latest movies and dissecting them over dinner afterward. Jeff was funny, smart, a technological whiz. In fact, the least interesting thing about him was that he happened to be gay.

Gay rights is not something most of us think about – because most of us happen to have been born straight. But imagine how you'd feel if you were told that it was unnatural to fall in love with someone of the opposite gender. If you weren't allowed to get married. If you couldn't adopt a child with your partner, or become a troop leader for the Boy Scouts. Imagine being a teenager who's bullied because of your sexual orientation; or being told by your church that you are immoral. In America, this is the norm for millions of LGBTQ individuals.

Those opposed to gay rights often say that they have nothing against the individuals themselves – just their desire want to redefine marriage as something other than a partnership between a man and a woman. On the other side are same-sex couples and their friends and families, who argue that they deserve the same rights as heterosexual couples. The result is a country bitterly divided along the fault line of a single, contentious issue.

People are always afraid of the unknown – and banding together against the Thing That Is Different From Us is a time-honored tradition for rallying the masses. I've noticed that most people who oppose gay rights don't have a personal connection to someone who is gay. On the other hand, those who have a gay uncle or a lesbian college professor or a transgendered supermarket cashier are more likely to support gay rights, because the Thing That Is Different From Us has turned out to be, well, pretty darn normal. Instead of plotting the demise of the traditional family, as some politicians and religious leaders would like you to believe, gay folks mow their lawns and watch American Idol and videotape their children's dance recitals and have the same hopes and dreams that their straight counterparts do.

When I started writing SING YOU HOME, I wanted to create a lesbian character that readers could truly get to know. Zoe Baxter is a woman who – along with her husband Max – has been trying to get pregnant for years. After many failed IVF attempts she finally conceives – only to lose the baby. The tragedy is the final nail in the coffin of her strained marriage, and she and Max divorce. To cope, Zoe throws herself into her career as a music therapist. When Vanessa, a guidance counselor, asks her to work with a suicidal teen, their relationship moves from business to friendship and then – to Zoe's surprise – blossoms into love. As she begins to think of having a family again, she remembers that there are still frozen embryos at the IVF clinic that were never used by herself and Max.

Meanwhile, Max has drunk himself into a downward spiral – until he is redeemed by an evangelical church, whose charismatic pastor has vowed to fight the "homosexual agenda" in America. But the mission becomes personal for Max when Zoe and her same-sex partner ask permission to raise his unborn child.

What does it mean to be gay today, in America? How do we define a family? Those are two questions I hoped to answer while writing SING YOU HOME. I began by speaking to several same-sex couples, who shared their relationships and their sex lives and their struggles. Some of these people knew their sexual orientation in childhood; some – like Zoe – had same-sex relationships after heterosexual ones. Then I interviewed representatives from Focus on the Family, a conservative Christian group that supports the Defense of Marriage Act, opposes gay adoption, and offers seminars to "cure" gay people of same-sex attraction. Like Pastor Clive in my novel, their objection to homosexuality is biblical. Snippets from Leviticus and other Bible verses form the foundation of their anti-gay platform; although similar literal readings should require these people to abstain from playing football (touching pigskin) or eating shrimp scampi (no shellfish). When I asked Focus on the Family if the Bible needs to be taken in a more historical context, I was told absolutely not – the word of God is the word of God. But when I then asked where in the Bible was a list of appropriate sex practices, I was told it's not a sex manual – just a guideline. That circular logic was most heartbreaking when I brought up the topic of hate crimes. Focus on the Family insists that they love the sinner, just not the sin – and only try to help homosexuals who are unhappy being gay. I worried aloud that this message might be misinterpreted by those who commit acts of violence against gays in the name of religion, and the woman I was interviewing burst into tears. "Thank goodness," she said, "that's never happened." I am sure this would be news to the parents of Matthew Shepherd, Brandon Teena, Ryan Keith Skipper, or August Provost – just a few of those murdered due to their sexual orientation - or the FBI, which reports that 17.6 percent of all hate crimes are motivated by sexual orientation, a number that is steadily rising. And it's not just in the US: in Iran, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, and parts of Africa, being gay is punishable by death.

Yet as eye-opening as all this research was, something happened during the writing of SING YOU HOME that truly made the subject hit home. My son Kyle, a brilliant, talented teenager, was applying to colleges while I was working on the book. One day, he brought me his finished application to read.

The essay was about being gay.

Did I know Kyle was gay before he came out in his essay? Well, I'd had my suspicions since he was five. But it was his discovery to make, and to share. I wasn't surprised, but I was so happy for him – for being brave enough to be true to himself, and to admit that truth to his family. My husband gave him a huge hug. Kyle's little sister shrugged and said, "So?" And his younger brother still calls to task those who carelessly say, "That's so gay," reminding them it's not a pejorative term.

Learning that Kyle was gay didn't change the way I felt about him. He was still the same incredible young man he'd been before I read that essay. I didn't love him any less because he was gay; I couldn't love him any more if he weren't. In the aftermath, I saw him blossom, finally comfortable in his own skin, because he wasn't living a lie anymore. Yet, as a mom, I had my worries – not because of Kyle's sexual orientation, but because the rest of the world might not be as accepting as our family. Because one day, when he least expects it, he's going to be called a "faggot." Because – simply due to the way his brain is wired – life is going to be more complicated.

Kyle is now a sophomore at Yale University – which has a thriving gay community and a culture of acceptance. His boyfriend is a smart, sweet guy who has accompanied us on vacations and who makes my son incredibly happy. Still, it breaks my heart to know that, unlike Kyle, there are teenagers today who cannot come out to their parents because of deep-seated prejudice -- which is too often cloaked in the satin robes of religion. Gay teens are four times as likely to attempt suicide as straight teens. I wish they knew that there's nothing wrong with them; that they are just a different shade of normal.

If I had any one great hope for SING YOU HOME, it would be to open the minds of those who have them closed tightly shut against those who are different – so that one day, my son's children will live in a world where being gay does not mean you're denied the 1138 federal rights automatically guaranteed by marriage. I hope they are just as puzzled as I am now when I see old photos of racially segregated schools and water fountains, and I wonder how could it possibly have taken so long for this country to come to its senses? I hope the religious leaders of their generation focus on the best literal interpretation of their Bible: Love your neighbor as yourself. But most of all, I hope that SING YOU HOME reminds people that while homosexuality is not a choice – homophobia is. Why not opt for tolerance and kindness instead?

"Never one to shy away from controversial issues, this time Picoult tackles gay rights, reproductive science, and the Christian right. She forces us to consider both sides of these hot topics with her trademark impeccable research, family dynamics, and courtroom drama. Sure to be a hit with her myriad fans and keep the book clubs buzzing!"

—Library Journal

Q + A

Book club discussion questions for Sing You Home

- Why does Picoult use a quotation from Thomas Jefferson for the book's epigraph? How can his message be interpreted in the context of the novel's events?

- Every life has a soundtrack. Name a song that brings back a memory of a time or place. Does it matter how much time has passed?

- The author skillfully presents the struggle couples with fertility issues have with IVF. Have you had any experience with this? Any insights to share?

- After reading each chapter, listen to the corresponding track on the CD. Why is the ending of Sing You Home so poignant?

- "There was no room in my marriage for me anymore, except as genetic material." (p. 51) Why does Max give up on his relationship with Zoe? Is his weak, or callous – or in any way justified? How has his experience of infertility and IVF affected him? How do Max and Zoe differ in their handling of disappointment and grief? Do you think they would have stayed together if they hadn't lost their baby?

- Pastor Clive seems to embody the very essence of fundamentalist religion. How does he make you feel?

- 7. "This may be news to you, Reid…but God doesn't vote Republican." (p. 75) What does Zoe mean by this? How does religion relate to the public worlds of politics, education, and the legal system in SING YOU HOME? To what extent is there – and should there be – a separation of church and state?

- Do you think it's a different world now than the one when Matthew Shepard was killed in Wyoming? Discuss.

- So much of a friendship is like a love affair". (p. 129) Agree? Disagree?

- A statement of religion: "I don't begrudge people the right to believe in whatever they believe, but I don't like having those same beliefs forced on me." (p.129) Discuss.

- "The music we choose is a clear reflection of who we really are". (p. 135) What songs would be on a mix tape that describes you?

- How does Zoe's first session with Lucy end? Do you think you could deal with Lucy?

- The author writes an excellent scene describing the intimacy between Zoe and Vanessa. Had you thought about it in those terms?

- Zoe and Vanessa have different experiences when they come out to their mothers. Discuss. How do you think you'd react?

- Max struggles with his new religious belief when Liddy miscarries again. Do you understand his struggle? How would you handle the conflict?

- Max takes Pauline with him to talk to Zoe. The author really gets to the crux of the issue when Vanessa speaks up. (p. 198) What is your opinion of Pauline's beliefs about homosexuality? Discuss.

- In your opinion, who most deserves the embryos: Max or Zoe? Why?

- In what ways does Liddy's reaction to snow, and her B-movie habit, inform her character?

- "…it's not gender that makes a family; it's love. You don't need a mother and a father; you don't necessarily even need two parents. You just need someone who's got your back". (p. 319) Discuss.

- Lucy gets angry at Zoe because Zoe won't tell Lucy about her personal life. Is Zoe right to not say anything?

- There are several groups of spectators in the courtroom on the opening day. With which group would you be sitting?

- When Reid is on the stand, what does Zoe find out about how Max met the cost of the last session of IVF? Why is this important?

- What happens between Max and Liddy? Are you surprised?

- Pastor Cline uses the Bible during his testimony and Angela uses it to contradict him. Do you believe, as Clive does, that what is in the Bible is immutable? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Why does Lucy tackle Pastor Clive? What does Zoe reveal in the ensuing conversation with Lucy? How does Lucy react?

- "Atheism, I realize, is the new gay. The thing you hope no one finds out about you-because of all the negative assumptions that are sure to follow." (p. 414) Agree? Disagree? Discuss.

- Both Zoe and Vanessa have secrets in their pasts. Are the secrets relevant to their relationship? To the trial?

- We find out Lucy's relationship to Pastor Clive. Were you surprised? Do you think she outed Zoe?

- The decision of who gets the embryos is made. (p. 461) Did Max do the right thing?

- What do you believe constitutes a family, a good parent?

- Has your opinion changed in any way about gay rights as a result of reading this book? If so, how?

PRAISE

What others are saying about Sing You Home

"Jodi Picoult's novels do not gather dust on the bedside table. They are gobbled up quickly and the readers want more. Sing You Home... is already flying off the shelves...You have to admire Picoult's grace under pressure. By throwing us into these debates she gives her readers the gift of faith in a higher justice — not the law, God or modern medicine but human goodness."

—LA Times

" Picoult...has crafted another winner. [She] cleverly examines the modern world of reproductive science, how best to nurture a child, and what, exactly, being a family means. "

—PEOPLE magazine, 3 1/2 stars

"What Picoult does best is bring audiences inside the mind, body and soul of each of her characters --- real people with the same hopes and dreams as anyone else. Regardless of where you stand on the issue of same-sex marriage and the ability of these couples to raise children, you cannot help but be compelled by the desires of Zoe, Max and Vanessa. The court case and its outcome is continuously unpredictable and will have readers glued to their chairs right up to the startling conclusion."

—BookReporter.com

"Picoult has written an immensely entertaining melodrama with crackerjack dialogue that kept me happily indoors for an entire weekend. [She]knows how to tell a killer story."

—USA Today

"Jodi Picoult has created almost a craving among fans for her novels blending the domestic with of-the-moment social issues. In SING YOU HOME, Zoe and Max Baxter are a happy-in-love couple until their marriage flounders after a series of failed fertility treatments. Soon enough, Max is a down-and-out alcoholic—until he's embraced by the pastor from a powerhouse evangelical church. While Zoe continues to thrum her healing notes on the cello as a music therapist, she finds love with another woman. Still obsessed with having a child, though close to penniless at 40, she asks Max for the right to implant her partner with their remaining frozen embryos. His newfound religiosity (and his pastor) won't allow it. The novel puts it to a judge to determine where justice lies, but really the decision is rendered by Picoult, once again making the case for human kindness. That's why her readers love her so."

—NY Daily News

"Sing [You Home] deftly personalizes the political, delivering a larger message of tolerance that's difficult to fault."

—Entertainment Weekly

"So personal that it feels autobiographical, Picoult's novel uses music (including original songs on an accompanying CD) to buoy the protagonist, a music therapist, through the throes of sexual experimentation, miscarriages, and family trauma."

—Ms. Magazine

"Usually Picoult's novels focus on one wham-bang topic that leads to a heavy dose of drama, litigation, and twists and turns. This time Picoult tackles two provocative issues— infertility and gay marriage.... Gripping, powerful—and bound to be talked about."

—Family Circle

"Popular author Picoult tackles the controversial topic of gay rights in her latest powerful tale…Told from the perspectives of all three major characters, Picoult's gripping novel explores all sides of hot-button issue."

—Booklist

March 10, 2011...

Sing You Home debuts at #1 on the USA Today book list, and at #1 on the NYT print & eBook list!

SING YOU HOME is a finalist for a NH Literary Award

An excerpt from Sing You Home

ZOE

One sunny, crisp Saturday in September when I was seven years old, I watched my father drop dead. I was playing with my favorite doll on the stone wall that bordered our driveway while he mowed the lawn. One minute he was mowing, and the next, he was face-first in the grass as the mower propelled itself in slow-motion down the hill of our backyard.

I thought at first he was sleeping, or playing a game. But when I crouched beside him on the lawn, his eyes were still open. Damp cut grass stuck to his forehead.

I don't remember calling for my mother, but I must have.

When I think about that day, it is in slow motion. The mower, walking alone. The carton of milk my mother was carrying when she ran outside, which dropped to the tarred driveway. The sound of round vowels as my mother screamed into the phone to give our address to the ambulance.

My mother left me at the neighbor's house while she went to the hospital. The neighbor was an old woman whose couch smelled like pee. She offered me chocolate-covered peppermints that were so old the chocolate had turned white at the edges. When her telephone rang I wandered into the backyard and crawled behind a row of hedges. In the soft mulch, I buried my doll and walked away.

My mother never noticed that it was gone – but then, it barely seemed that she acknowledged my father being gone, either. She never cried. She stood stiff-backed through my father's funeral. She sat across from me at the kitchen table that I still sometimes set with a third place for my father, as we gradually ate our way through chipped beef casserole and mac-and-cheese-and franks, sympathy platters from my father's colleagues and neighbors who thought food could make up for the fact that they didn't know what to say. When a robustly healthy 42-year-old dies of a massive heart attack, the grieving family is suddenly contagious. Come too close, and you might catch our bad luck.

Six months after my father died, my mother – still stoic - took his suits and shirts out of the closet they shared and brought them to Goodwill. She asked the liquor store for boxes and she packed away the biography that he had been reading, which had been on the nightstand all this time; and his pipe, and his coin collection. She did not pack away his Abbott and Costello videos, although she always had told my father that she never really understood what made them funny.

My mother carried these boxes to the attic, a place that seemed to trap cluster flies and heat. On her third trip up, she didn't come back. Instead, what floated downstairs was a silly, fizzy refrain piped through the speakers of an old record player. I could not understand all the words, but it had something to do with a witch doctor telling someone how to win the heart of a girl.

Ooo eee ooh ahh ahh, ting tang walla walla bing bang, I heard. It made a laugh bubble up in my chest, and since I hadn't laughed all that much lately, I hurried to the source.

When I stepped into the attic, I found my mother weeping. "This record," she said, playing it over again. "It made him so happy."

I knew better than to ask why, then, she was sobbing. Instead, I curled up beside her and listened to the song that had finally given my mother permission to cry.

Every life has a soundtrack.

There is a tune that makes me think of the summer I spent rubbing baby oil on my stomach in pursuit of the perfect tan. There's another that reminds me of tagging along with my father on Sunday mornings to pick up the New York Times. There's the song that reminds me of using fake ID to get into a nightclub; and the one that brings back my cousin Isobel's sweet sixteen, where I played Seven Minutes in Heaven with a boy whose breath smelled like tomato soup.

If you ask me, music is the language of memory.

Wanda, the shift nurse at Shady Grove Assisted Living, hands me a visitor pass, although I've been coming to the nursing home for the past year to work with various clients. "How is he today?" I ask.

"The usual," Wanda says. "Swinging from the chandelier and entertaining the masses with a combination of tap dancing and shadow puppets."

I laugh. In the twelve months I've been Mr. Docker's music therapist, he's interacted with me twice. Most of the time, he sits in his bed or a wheelchair, staring through me, completely unresponsive.

When I tell people I am a music therapist, they think it means I play guitar for people who are in the hospital – that I'm a performer. Actually, I'm more like a physical therapist, except instead of using treadmills and grab bars as tools, I use music. When I tell people that, they usually dismiss my job as some New Age BS.

In fact, it's very scientific. In brain scans, music lights up the medial pre-frontal cortex and jump starts a memory that starts playing in your mind. All of a sudden you can see a place, a person, an incident. The strongest responses to music – the ones that elicit vivid memories – cause the greatest activity on brain scans. It's for this reason that stroke patients can access lyrics before they remember language; why Alzheimer's patients can still remember songs from their youth.

And why I haven't given up on Mr. Docker yet.

"Thanks for the warning," I tell Wanda, and I pick up my duffel, my guitar and my djembe.

"Put those down," she insists. "You're not supposed to be carrying anything heavy."

"Then I'd better get rid of this," I say, touching my belly. In my twenty-eighth week, I'm enormous – and I'm also completely lying. I worked way too hard to have this baby to feel like any part of the pregnancy is a burden. I give Wanda a wave, and head down the hall to start today's session.

Usually my nursing home clients meet in a group setting, but Mr. Docker is a special case. A former CEO of a Fortune 500 company, he now lives in this very chic eldercare facility, and his daughter Mim contracts my services for weekly sessions. He's just shy of eighty, has a lion's mane of white hair, and gnarled hands that apparently used to play a mean jazz piano.

The last time Mr. Docker gave any indication that he was aware I shared the same physical space as him was two months ago. I'd been playing my guitar, and he smacked his fist against the handle of his wheelchair twice. I am not sure if he wanted to chime in for good measure or was trying to tell me to stop -- but he was in rhythm.

I knock and open the door. "Mr. Docker?" I say. "It's Zoe. Zoe Baxter. You feel like playing a little music?"

Someone on staff has moved him to an armchair, where he sits looking out the window. Or maybe just through it – he's not focusing on anything. His hands are curled in his lap like lobster claws.

"Right!" I say briskly, trying to maneuver myself around the bed and the television stand and the table with his untouched breakfast still intact. "What should we sing today?" I wait a beat, but am not really expecting an answer. "You Are My Sunshine?" I ask. "Tennessee Waltz?" I try to extract my guitar from its case in a small space beside the bed, which is not really big enough for my instrument and my pregnancy. Settling the guitar awkwardly on top of my belly, I start to strum a few chords. Then, on second thought, I put it down.

I rummage through the duffel bag for a maraca – I have all sorts of small instruments in there, for opportunities just like this. I gently wedge it into the curl of his hand. "Just in case you want to join in." Then I start singing softly. "Take me out to the ballgame; take me out with the…"

The end, I leave hanging. There's a need in all of us to finish a phrase we know, and so I'm hoping to get him to mutter that final "crowd." I glance at Mr. Docker, but the maraca remains clenched in his hand, silent.

"Buy me some peanuts and cracker jack; I don't care if I never get back."

I keep singing as I step in front of him, strumming gently. "Let me root, root, root for the home team; if they don't win it's a shame. For it's one, two, three –"

Suddenly Mr. Docker's hand comes flying up and the maraca clips me in the mouth. I'm so surprised I stagger backward, and tears spring to my eyes. I can taste blood. I press my sleeve to my cut lip, trying to keep him from seeing that he's hurt me. "Did I do something to upset you?"

Mr. Docker doesn't respond.

The maraca has landed on the pillow of his bed. "I'm just going to reach behind you, here, and get the instrument," I say carefully, and as I do, he takes another swing at me. This time, I stumble backward, crashing into the table and overturning his breakfast tray.

"What is going on in here," Wanda cries, bursting through the door. She looks at me, at the mess on the floor, and then at Mr. Docker.

"We're okay," I tell her. "Everything's okay."

Wanda takes a long, pointed look at my belly. "You sure?"

I nod, and she backs out of the room. This time, I sit gingerly on the edge of the radiator in front of the window. "Mr. Docker," I ask softly, "what's wrong?"

When he faces me, his eyes are bright with tears. He lets his gaze roam the room – from its institutional curtains to the emergency medical equipment in the cabinet behind the bed to the plastic pitcher of water on the nightstand. "Everything," he says tightly.

I think about this man, who once was written up in Money and Fortune. Who used to command thousands of employees and whose days were spent in a richly paneled corner office with a plush carpet and a leather swivel chair. For a moment, I want to apologize for taking out my guitar, for unlocking his blocked mind with music.

Because there are some things we'd rather forget.

The doll that I buried at a neighbor's house on the day my father died was called Sweet Cindy. I had begged for her the previous Christmas, completely suckered by the television ads that ran on Saturday mornings between Wonderama and The Patchwork Family. Sweet Cindy could eat and drink and poop and tell you that she loved you. "Can she fix a carburetor?" my father had joked, when I showed him my Christmas list. "Can she clean the bathroom?"

I had a history of treating dolls badly. I cut off my Barbie dolls' hair with fingernail scissors. I decapitated Ken, although in my defense that had been an accident involving a fall from a bicycle basket. But Sweet Cindy I treated like my own baby. I tucked her into a crib each night that was set beside my own bed. I bathed her every day. I pushed her up and down the driveway in a stroller we'd bought at a garage sale.

On the day of my father's death, he'd wanted to go for a bike ride. It was beautiful out; I had just gotten my training wheels removed. But I told my father that I was playing with Cindy, and maybe we could go later. "Sounds like a plan, Zo," he had said, and he started to mow the back lawn, and of course there was no later.

If I had never gotten Sweet Cindy for Christmas.

If I'd said yes to my father when he asked.

If I'd been watching him, instead of playing with the doll.

There were a thousand permutations of behavior that, in my mind, could have saved my father's life – and so although it was too late and I knew that, I told myself I'd never wanted that stupid doll in the first place; that she was the reason my father wasn't here anymore.

The first time it snowed after my father died, I had a dream that Sweet Cindy was sitting on my bed. Crows had pecked out her blue-marble eyes. She was shivering.

The next day I took a garden spade from the garage and walked to the neighbor's house where I'd buried her. I dug up the snow and the mulch from half of the hedge row, but the doll was gone. Carried away by a dog, maybe, or a little girl who knew better.

I know it's stupid for a 38 year old woman to connect a foolish act of grief with four unsuccessful cycles of IVF, two miscarriages, and enough infertility issues to bring down a civilization – but I cannot tell you how many times I've wondered if this is some kind of karmic punishment.

If I hadn't so recklessly abandoned the first baby I ever loved, would I have a real one by now?

By the time my session with Mr. Docker ends, his daughter Mim has rushed from her ladies' auxiliary meeting to Shady Grove. "Are you sure you didn't get hurt?" she says, looking me over for the hundredth time.

"Yes," I tell her, although I suspect her concern has more to do with a fear of being sued than genuine concern for my well-being.

She rummages in her purse and pulls out a fistful of cash. "Here," Mim says.

"But you've already paid me for this month –"

"This is a bonus," she says. "I'm sure, with the baby and everything, there are expenses."

It's hush money, I know that, but she's right. Except that the expenses surrounding my baby have less to do with car seats and strollers than with Lupron and Follistim injections. After five IVF cycles – both fresh and frozen – we have depleted all of our savings and maxed out our credit cards. I take the money and tuck it into the pocket of my jeans. "Thank you," I say, and then I meet her gaze. "What your father did? I know you don't see it this way, but it's a huge step forward for him. He connected with me."

"Yeah, right on your jaw," Wanda mutters.

"He interacted," I correct. "Maybe in a less-than-socially-appropriate way…but still. For a minute, the music got to him. For a minute, he was here."

I can tell she doesn't buy this, but that's all right. I have been bitten by an autistic child; I have sobbed beside a little girl dying of brain cancer; I have played in tune with the screams of a child who has been burned over 80% of his body. This job…if it hurts me, I know I am doing it well.

"I'd better go," I say, picking up my guitar case.

Wanda nods. "See you next week."

"Actually, you'll see me in about two hours at the baby shower."

"What baby shower?"

I grin. "The one I'm not supposed to know about."

Mim reaches out her hand toward my protruding belly. "May I?" I nod. I know some pregnant women think it's an invasion of privacy to have strangers reaching to pat or touch you or offer parenting advice, I don't mind in the least. I can barely keep myself from rubbing my hands over the baby myself, from being magnetically drawn to the proof that this time, it is going to work.

"It's a boy," she announces.

I have been thoroughly convinced that I'm carrying a girl. I dream in pink. I wake up with fairytales caught on my tongue. "We'll see," I say.

I've always found it ironic that someone who has trouble getting pregnant begins in vitro fertilization by taking birth control pills. It is all about regulating an irregular cycle, in order to begin an endless alphabet soup of medications: three ampoules each of FSH and hMG - Follistim and Repronex- injected into my backside twice a day by Max – a man who used to faint at the sight of a needle and who now, after six years, can give me a shot with one hand and pour coffee with the other. Six days after starting the injections a transvaginal ultrasound measured the size of my ovarian follicles, and a blood test clocked my estradiol levels. That led to Antagon, a new medication meant to keep the eggs in the follicles until they were ready. Three days later: another ultrasound and blood test. The amount of Follistim and Repronex were reduced – one ampoule of each at morning and night – and then two days later, another ultrasound and blood test.

One of my follicles measured 21mm. One measured 20mm. And one was 19mm.

At precisely 8:30 PM Max injected 10,000 units of hCG into me. Exactly 36 hours later, those eggs were retrieved.

Then ICSI – intracytoplasmic sperm injection – was used to fertilize the egg with Max's sperm. And three days later, with Max holding my hand, a vaginal catheter was inserted into me and we watched the embryo transfer on a blinking computer monitor. There, the lining of my uterus looked like sea grass swaying in the current. A little white spark, a star, shot out of the syringe and fell between two blades of grass. Another. A third. We celebrated our potential pregnancy with a shot of progesterone in my butt.

And to think, some people who want to have a baby only need to make love.

There are games. Estimate-Zoe's-Belly-Size; a purse scavenger hunt (who would have guessed that my mother had an overdue utility bill in her bag?), a baby sock matching relay, and, now, a particularly disgusting foray where baby diapers filled with melted chocolate are passed around for identification by candy bar brand.

Even though this isn't really my cup of tea, I play along. My part-time bookkeeper, Alexa, has organized the whole event – and has even gone to the trouble of rounding up guests: my mother, my cousin Isobel, Wanda from Shady Groves and another nurse from the burn unit of the hospital where I work, and a guidance counselor named Vanessa who contracted me to do music therapy earlier this year with a profoundly autistic ninth grader.

It's sort of depressing that these women, acquaintances at best, are being substituted for close friends – but then, if I'm not working, I'm with Max. And Max would rather be run over by his own lawn mowing machines than identify chocolate feces in a diaper. I try not to focus on how depressing it is to be 38 and not have any close female friends, and instead watch Wanda peer into the Pampers. "Snickers?" she guesses incorrectly.

Vanessa gets the diaper next. She's tall, with a short black bob and piercingly blue eyes. The first time I met her she invited me into her office and gave me a blistering lecture on how the SATs were a conspiracy by the College Board to take over the world $80 at a time. Well? she said when she finally stopped for a breath. What do you have to say for yourself?

I'm the new music therapist, I told her.

She had blinked at me, and then looked down at her calendar, and flipped the page backward. Ah, she said. Guess the rep from Kaplan is coming tomorrow.

Vanessa doesn't even glance down at the diaper. "I'm going to say Mounds. Two, to be exact."

I burst out laughing, but I'm the only one. Alexa looks like she's going to cry. My mother intervenes, collecting the diaper from Vanessa's placemat. "What about Name That Baby?" she suggests.

I feel a twinge in my side and absently rub my hand over the spot.

My mother reads from a paper Alexa has printed off the internet. "A baby lion is a…"

My cousin's hand shoots up. "Cub!" she yells out.

"Right! A baby fish is a….?"

"Caviar?" Vanessa suggests.

"Fry," Wanda says.

"That's a verb," Isobel argues.

"I'm telling you, I saw it on Who Wants to Be a Millionnaire –"

Suddenly I am seized by a cramp so intense that all the breath rushes out of my body and I jackknife forward.

"Zoe?" My mother's voice seems far away. I struggle to my feet.

Twenty-eight weeks, I think. Too soon.

Another current rips through me. As I fall against my mother, I feel a warm gush between my legs. "My water," I whisper. "I think it just broke."

But when I glance down, I am standing in a pool of blood.

Missing You Convince Myself Get Over You Baby Crying Mom Singing Ellen

Source: https://www.jodipicoult.com/sing-you-home.html

0 Response to "Missing You Convince Myself Get Over You Baby Crying Mom Singing Ellen"

Post a Comment